Reliable electricity is becoming even more reliable

Your electricity is on almost all the time. You knew that.

But you might not know how much of the time it’s on. And that the amount of time it’s on has been getting better every year.

Electricity has become so reliable that the numbers for a typical American home sound crazy. For most people, the total amount of time without power (an outage) is less than two hours a year—that means their electricity is on 99.977169 percent of the time.

“You can’t have 100 percent reliability all the time on something as large as an electric distribution system,” says Tony Thomas, principal engineer at the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association. And although U.S. electric service on-time is just a decimal point from perfect, Thomas says, “Reliability has been getting much better.”

To understand the improvements in electric utility reliability, you need to be introduced to what Thomas says are known as “the three sisters:” the acronyms SAIDI, CAIDI and SAIFI.

Those stand for different ways to measure how power outages affect consumers. Here’s what they mean:

SAIDI shows how long an average customer goes without power during a year. It stands for System Average Interruption Duration Index. It’s calculated by dividing all of a utility’s power interruptions by the number of customers that utility serves. Analysts caution against citing a national average SAIDI because of the huge differences in utilities across the country and how data is collected. But a report from the Institute for Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) puts the typical customer as being without power 115 minutes a year.

SAIDI numbers do not include extremely long or very short outages, since they could drastically skew the results among utilities and make the numbers less useful. Extremely long outages, like those caused by a major storm, can sometimes last more than a day. The short outages that are not included in SAIDI are, for example, cases like a utility circuit breaker quickly opening and closing.

SAIFI shows how often the power goes out for each customer. It stands for System Average Interruption Frequency Index. It’s calculated by dividing the number of customer interruptions by the number of customers.

CAIDI shows the average time it takes to restore power after an outage. It stands for Customer Average Interruption Duration Index. It’s calculated by dividing SAIDI by SAIFI.

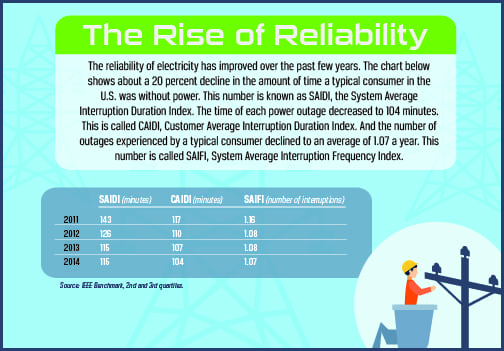

All three of those reliability measures have been improving in the past few years, according to IEEE reports. The amount of time a utility customer was without electricity for the year (SAIDI) declined about 20 percent in the most recent four years of figures, from 143 minutes in 2011, to 115 minutes in 2014.

The number of outages per typical consumer in a year (SAIFI) went down from 1.16 to 1.07. And how long each of those outages lasted (CAIDI) declined from 117 minutes in 2011 to 104 minutes in 2014.

Thomas credits advances in utility technology for those improvements.

More and more mechanical electric meters are being replaced with automated smart meters that do more than just measure the bulk use of electricity coming to the meter at your house. They can also monitor whether electricity is delivered to your house at all, as well as the voltage quality of that electricity.

“With automated meters, utilities can know a consumer is out of power before the consumer knows it,” Thomas says.

Another step toward utilities spotting and solving outages faster is the more widespread adoption of high-tech monitoring systems. These SCADA systems (it stands for Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition) are typically set up as several computer monitors in a control room, each showing a different view of the utility’s service area, including weather maps and detailed schematics of each power line, substation and home or business served.

“Prices have dropped for SCADA systems, just like for all software in the last few years,” Thomas says. “Utility technology has gotten a lot better in the last 10 years.”

Thomas credits electric cooperatives with making special use of technology to overcome the barriers of long distances between consumer-members. Outages and other routine changes in power flow can be more quickly and easily addressed remotely, without having to make a long drive to a home or substation.

“Rural electric co-ops have done an amazing job of adopting technology and putting it to use,” Thomas says. “And all this technology just translates into better operation of the electric system.”

Paul Wesslund writes on cooperative issues for the National Rural Electric Cooperative Association, the Arlington, Va.-based service arm of the nation’s 900-plus consumer-owned, not-for-profit electric cooperatives.